[Adapted from a presentation given at a Faculty/Staff Luncheon at Randolph-Macon College on November 7, 2017.]

The academic library is a challenge to discuss in mixed company. To those in the know, the academic library is a dynamic place of innovation, the location of epic battles for information literacy, freedom of information, preservation, open access, and educational technology. To others, the academic library is an obsolete warehouse, facing inevitable decline.

Members of the Randolph-Macon College community have likely noticed emails stating that the library is discarding microfilm and microfiche in favor of new digital resources such as The New York Times Archive Online, and The Economist Archive. Many have also realized that there aren’t as many books on the shelves as there used to be, as we’re weeding our book collection and discarding resources that haven’t been used in many years. These are indicative of broader trends in academic libraries, and it seems worthwhile to explain what we’re thinking when we do that.

Primary Goals of the Library

It may be most helpful to begin by thinking about the role that the library has traditionally played on college and university campuses as the intellectual center, or the heart, of the campus. The library has always had three primary goals:

- Keeping things for a long time

- Providing the information that the current community needs

- Helping members of the community find and use the information that was made available 1

Let’s look briefly at each of these goals.

Preservation

The library preserves the heritage and traditions of an institution, keeping both qualitative and quantitative data that can tell the story not only of college life in the mid-1800s, but also the necessarily record of changes to policies or curriculum.

Information

Information needs change regularly, and the library has always tried to be responsive, even anticipatory, to what students, faculty, and staff need, whether it’s books, journals, or data. When word processing first took off and before everyone had a personal computer, computers were available in the library. That was what was needed. As the needs of the community change, the information provided by the library changes.

The size and quality of the local collection have historically been very, very important, because it used to be more difficult to find books not held in the collection. Before Amazon, the options were scouring local new and/or used bookstores or using interlibrary loan to request the book from another academic library, an option that could take weeks or even months.

Access & Use

Making sure the community could use the information years ago really meant serving as de facto gatekeepers. Users of information almost always needed to go through the library to access the information, so there was a fair amount of control over what and how information was used. It was also possible to simply wait for students to come to the library—eventually, they had to—and then they could be helped if needed.

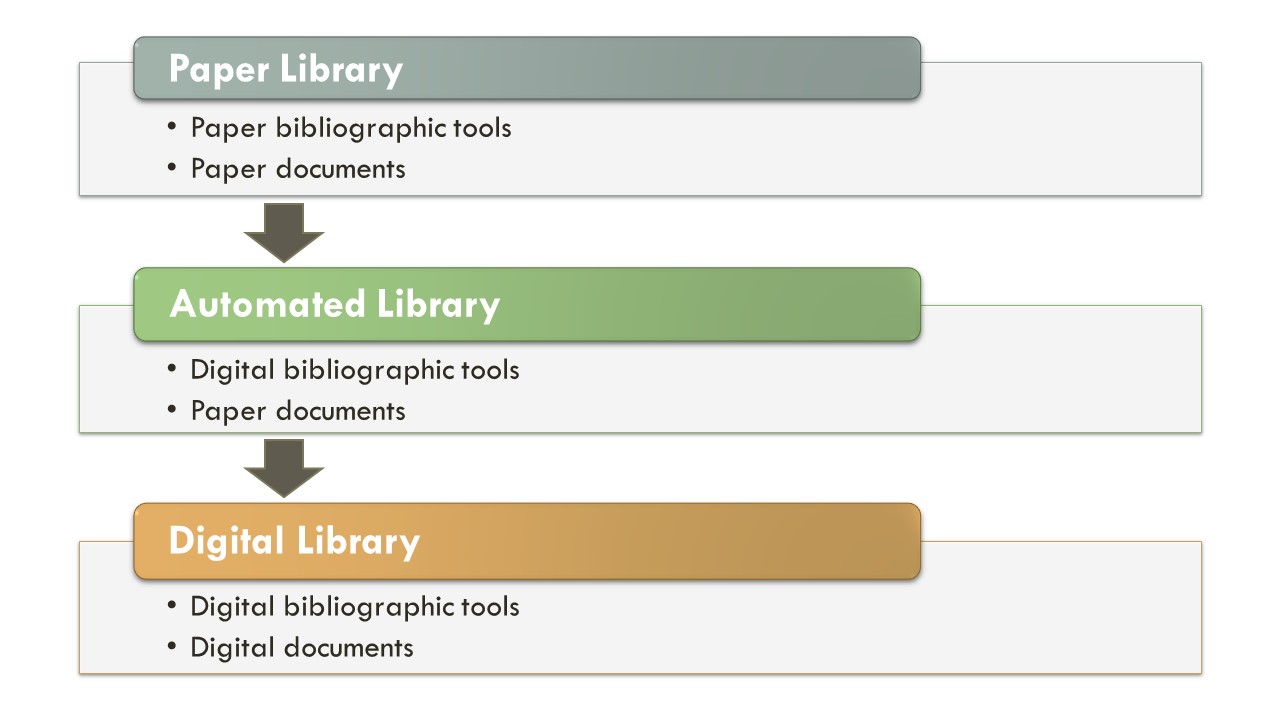

Paper to Digital2

We now find ourselves in a period of transition. For hundreds of years, the academic library has existed in print. Papyrus, scrolls, vellum, wood pulp. These things were physical items that could be stored, retrieved, opened, read, preserved. They took up physical space, could only be in one location at a time, and would typically only be used by one person at a time (reading aloud does happen, but it is unusual for two people to independently read the same item at the same time).

Now, in the space of forty (or so) years, we find ourselves in a very different environment.

Few libraries have transitioned to a fully digital library model as of this date (Nov. 2017). Some resources fit the digital format well: encyclopedias, dictionaries, and almanacs have been quickly replaced by digital options in which it is quick and easy to look up a discrete fact. Journals have transitioned well because they are made up of many individual articles. Edited volumes are transitioning fairly well, but monographs less so. There are also distinct differences among disciplines. The sciences have shifted quickly: they rely heavily on journal articles, and many books in the sciences are edited volumes. It’s not unusual to hear of science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM) libraries that are entirely paperless (e.g., UT-San Antonio, Florida Polytechnic). It’s important to note that these institutions still build libraries for their campuses, even though those libraries no longer house print books. The humanities are transitioning much less quickly, in part because of their dependence on the monograph. The transition in the social sciences falls between the two on the continuum.

There are other challenges facing the transition to a fully digital library: money to digitize and make electronically accessible material that is less in-demand, and the simple fact that some people like using and reading digital texts, while others do not. Even acknowledging that we are not fully digital, the implications of this shift have been huge.

- Both the amount of available information and the amount that a given library can provide have increased significantly.

- Despite what one would consider cost-saving digital publishing options, costs of one-time and subscription resources have continued to increase, often rising 6% per year or more.

- Smaller libraries often need to choose between owning resources and leasing them. With many budgets continuing to shrink or plateau, it can be a difficult decision to choose between owning 50 resources versus leasing 160,000.

- Scholarly communication is changing almost as quickly as the technology is. Scholarly communication is:

“The system through which research and other scholarly writings are created, evaluated for quality, disseminated to the scholarly community, and preserved for future use. The system includes both formal means of communication, such as publication in peer-reviewed journals, and informal channels, such as electronic listservs.”3

The line between formal and informal communication is blurring more and more. Disciplines are becoming more and more specialized. The role of peer‐review continues to be valuable, but is questioned frequently. How can a student learn to differentiate between a blog published by a notable scholar and a peer‐reviewed article by that same scholar? What should be collected and preserved by the library?

Within academic libraries, the topic of scholarly communication is usually discussed simultaneously with open access (OA). And this association with open access comes from the belief that scholarship is a public good that should be publicly available. As the price of formal scholarship continues to increase, putting scholarship behind paywalls that soon only elite institutions will be able to afford, academic libraries, particularly large, well-funded institutions, have been trying to break what essentially amounts to a monopoly on scholarship, by encouraging faculty to publish with OA publishers, and by devoting more resources to supporting OA publications, in some cases starting their own publishing endeavors. At institutions where the impact factor of a journal can decide whether or not a faculty member gets tenure, you can imagine that progress is slow!

- Libraries are facing competition they haven’t faced before: Google, Google Scholar, Google Books, Amazon, and Wikipedia are all readily available, free, and for many students indistinguishable from resources available through their library.

- Students, while in many ways the same as they have always been, are frequently:

- Overconfident in their ability to search (and find)

- Impatient, needing to have content available instantly

- Hesitant to ask for help

- Have misperceptions about libraries and librarians, and how both can help them succeed.

In part because of the changes that libraries have been undergoing in the past few decades, and because online resources both lack the dramatic appeal of physical resources and continue to become more expensive, academic libraries are being regularly asked to justify their existence. Library are more than just the books and journals they provide, of course, and they always have been. But in today’s assessment-conscious environment, research is being done to look at how libraries contribute to student success and retention.

A recent 3‐year project at over 200 post-secondary institutions looked at multiple library factors and their potential impacts on students’ academic outcomes.

-

- Students benefit from library instruction in their initial coursework.

- Library use increases student success.

- Collaborative academic programs and services involving the library enhance student learning.

- Information literacy instruction strengthens general education outcomes.

- Library research consultations boost student learning. 4

In light of all of these changes, how have the three primary goals of the library changed?

Preservation

In the digital library world, preservation of the College’s history remains an important part of the library’s mission, even as it has gotten more complex. What do we do with slides or VHS tapes as the technologies become obsolete? How do we preserve the website or the social media of the college in such a way that it can be used in a telling of the College’s history 50 years from now? For the first time, we need to make decisions about what is

worth preserving, rather than preserving everything, as has been the habit.

As more and more information is available and easily accessed, library collections, especially among similar types and sizes of institutions, will look more and more similar. The library collection at Randolph‐Macon College will not differ significantly from the collection at Hamden‐Sydney or Lynchburg. It will be the unique special collections that will really set the libraries of these institutions apart. They will provide unique research opportunities for students, and can attract faculty in a number of disciplines.

Information

The types and nature of information needed to support research have changed. We’re still purchasing print books in addition to online archives and databases, and this isn’t a function of our size and budget. Every library director I’ve talked to recently is still doing the same. But a technological solution invented next year could change that. So as we look to the future, we need to do so in a way that can continue to accommodate change. Because change is coming.

Access & Use

Finding information is no longer a problem. Now it is a question of finding the right information. We have moved from an environment of information scarcity to an environment of information overload. Students still need to learn how to tell a book citation from an article citation from an essay citation, and they still need to understand how to evaluate the information they’re finding to be able to tell the difference between a peer‐reviewed resource and “fake news.” But now they also need to know how to navigate constantly changing interfaces, while learning how to cite a tweet in their paper.

What we may think of as the “traditional” library, full of print journals, silent book stacks, students working alone on individual paper assignments, is likely gone for good. In its place is an academic library still preserving institutional history, providing information resources for its community, and teaching students how to access and use those resources. Academic libraries are striving to navigate a complicated environment, and to succeed, they need to be discussed in a much more nuanced way among librarians, faculty, students, campus leaders, and donors.

My next post will look at some of the specific pivots libraries are making to adjust to this new environment, and how a learning commons model in the McGraw-Page Library can support those changes.

1. Lewis, D. W. (2016). Reimagining the academic library. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.↩

2. Buckland, M. (1992). Redesigning library services: A manifesto. Chicago: American Library Association.↩

3. Association of College & Research Libraries. 2003. Principles and strategies for the reform of scholarly communication 1. Accessed 3 November 2017.↩

4. Association of College and Research Libraries. 2017. Academic library impact on student learning and success: Findings from assessment in action team projects. Prepared by Karen Brown with contributions by Kara J. Malenfant. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.↩

One thought on “The Library is Dead! Long Live the Library!”