[Adapted from a Faculty/Staff Luncheon presentation, November 7, 2017.]

Last month’s post discussed the ways in which the 21st-century academic library is similar and different from academic libraries of the past. This month we’re going to look at how many 21st-century libraries are adapting to these changes.

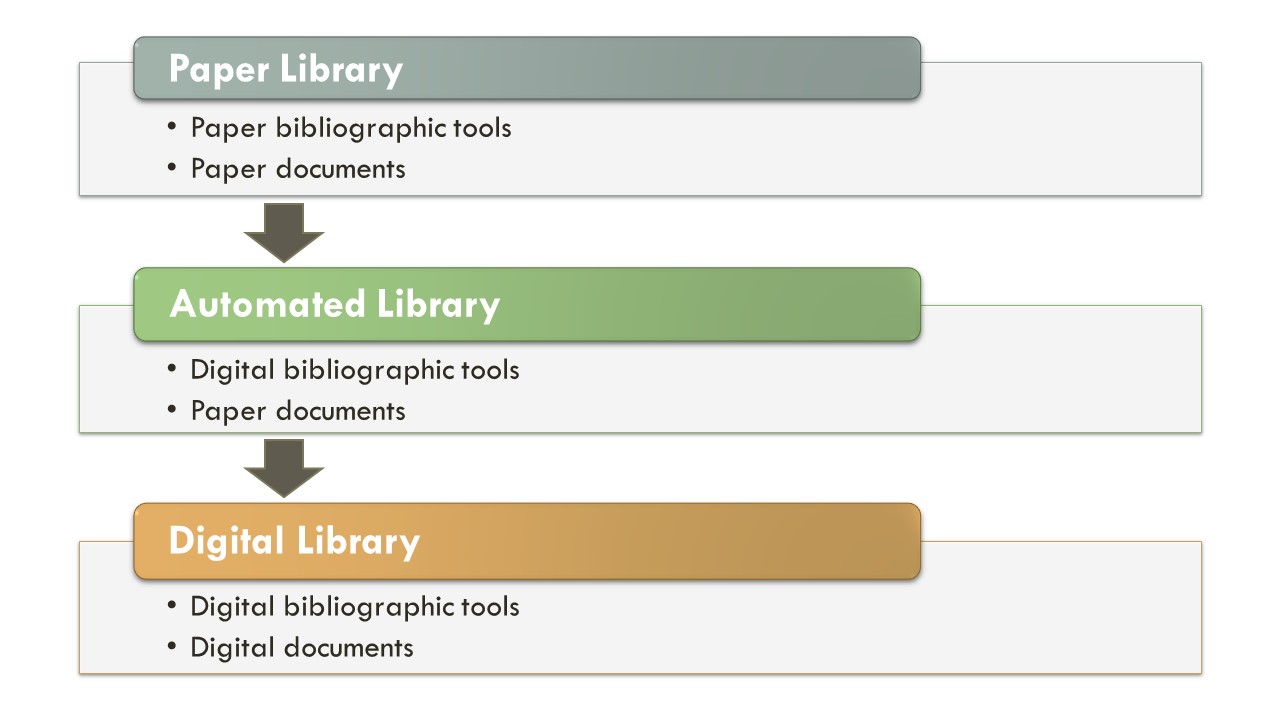

Paper to Digital

Many libraries, including McGraw-Page, are shifting more and more toward digital resources, and this trend is likely to continue. The culture of the library and the institution of which it is a part plays a huge role in determining what digital resources are purchased, how they are integrated into the rest of the collection, and how quickly this shift takes place. A medical library will likely shift more quickly to digital resources than will a residential liberal arts college. Space constraints encourage the acquisition of digital resources, while financial constraints can limit their acquisition. Usage patterns and preferences of faculty and students also come into play. The technology itself continues to develop, requiring libraries to be flexible in their approach. Some resources are not available digitally at all. One advantage to a major shift from print to digital resources can be a gain in space that can be repurposed to meet other needs.

Collections to Users

Libraries are also shifting away from their collections to become more focused on users and their needs. Because so much is available online, and because there are many (fast!) options for getting resources not available locally (e.g., document delivery, interlibrary loan, Amazon), developing a collection that will anticipate the needs of a college or university is no longer as essential as it once was.

The library has become more important as a place on campus. Several studies have confirmed that students view libraries as sacred spaces—that being in a library, even if not using library resources, makes students feel more “academic,” closer to the educational mission of the college 1. Which perhaps why using a library is positively associated with student success and retention.

The library is now a place that is expected to meet the space needs of the entire population. Students value the library as a place where it is possible to study without distraction. But it is also a place where the space and technology facilitate and encourage collaboration. It should inspire creativity and academic success as an intellectual center of campus, and be both a sacred space, that connects students to the academic mission of the college, as well as comfortable, a place where students can fall asleep on the couch.

This need to be everything to everyone creates obvious challenges, as the library tries to provide a variety of space, seating, and working options to meet those needs.

Passive to Proactive

Libraries are also shifting from passively waiting for users to come to them, to proactively reaching out. In some ways, this is a direct results of the competition that libraries now face. But it also comes from the teaching role that more and more libraries are embracing. Many academic libraries are now actively involved in:

- Making the community aware of available resources

- Connecting the community with those resources

- Supporting the use of those resources

Recognizing that students frequently struggle to know how to research, and that even faculty can easily forget about newly acquired resources, libraries are becoming more and more outward-facing with what they provide, accepting their role as educators on campus. The goal is to raise awareness of available resources and services, so that if a student encounters an issue they know where to go for the support they need.

Learning Commons

So how does the learning commons fit into this? The idea of a learning commons, or an information commons, has been a part of library conversations for almost 20 years. I see it as a natural extension of the shifts that libraries are making as they adjust to the new reality. The library used to focus almost exclusively on information seeking needs–collecting, finding, and helping the community use information of various kinds and in various formats. If students in a particular major don’t write many research papers, there’s no real need to come to the library. In reality, the library is crucial to the entire academic process. It’s not just about finding information, it’s about what you do with that information, and how you communicate what you’ve learned. Creating a product that communicates learning is integral to the educational process, and the library provides the technology, tools, and support to make that happen.

A learning commons can facilitate library involvement in student academic work by helping to combat the artificial divisions that exist among the elements of the academic endeavor. Class work, research, reading, writing and presentation creation, editing, and publication (here meant less formally as simply publicly sharing information) all work together to facilitate learning. Research is often best if grounded in the classwork that has already been done. But a trip to the library is seen as a separate event that isn’t really related to the classes that a student has been attending all semester. Tutoring is a natural part of going to classes, taking tests, writing papers, and pushing the boundaries of one’s knowledge. Career services is in many ways the culmination of what we do. Most students expect to get a job at some point after college. Why do we pretend that the education process and the process of getting a job are somehow unrelated?

It’s good for students to see the all elements of the academic endeavor together, to see their research, tutoring, writing, and creating in a similar context with The Edge, and what they hope to do when they graduate. Visualizing how the pieces are supposed to fit together in the end gives meaning to each step in the journey.

Ultimately, a learning commons would significantly improve R-MC’s academic support for students. It would bring almost all of their academic resources together into a single location, making support more coordinated and coherent.

Who would be involved?

A learning commons at Randolph-Macon College would include the McGraw-Page Library, the Higgins Academic Center (HAC), which is already located in the library building, the EDGE career center, the Office of International Education, the Honors program, and I.T.S.

The goal is not to simply co-locate these services, but to integrate them so that students can seamlessly move from one office to the next without realizing that they are interacting with separate organizations within the library.

What have we done so far?

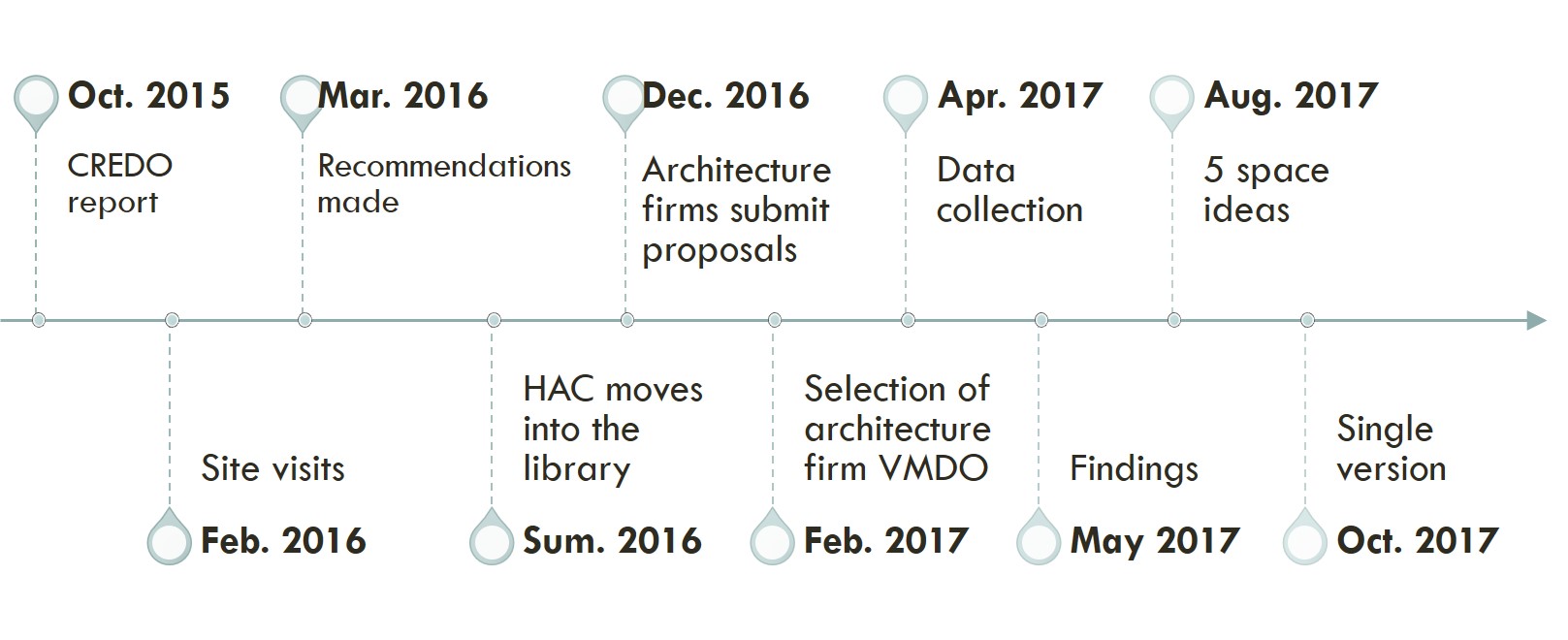

Below is the timeline for what has taken place thus far:

Oct. 2015 – CREDO report suggests moving HAC services into the library

Feb. 2016 – Site visits

Mar. 2016 – Memo regarding creating a learning commons, based

Sum. 2016 – HAC moves into the library

Dec. 2016 – 4 architecture firms gather information and submit proposals

Feb. 2017 – Presentations and selection of architecture firm VMDO

Apr. 2017 – Workshops, focus groups, data collection

May 2017 – Presentation of findings and initial recommendations

Aug. 2017 – Presentation of 5 possible space configurations

Oct. 2017 – Merging of attractive elements into a single version

What are the next steps?

The next steps are to create a shared vision of the learning commons space among the learning commons partners, and begin exploring funding options. We can then move forward with the details of the space renovation and addition.

If you’re interested in learning more about the learning commons project, please contact me at NancyFalcianiWhite [at] rmc.edu.

1. E.g., Jackson, H. L., & Hahn, T. B. (2011). Serving Higher Education’s Highest Goals: Assessment of the Academic Library as Place. College & Research Libraries, 72(5), 428–442.↩

Web 2.0 and the Political Mobilization of College Students investigates how college students’ online activities, when politically oriented, can affect their political participatory patterns offline. Kenneth W. Moffett and Laurie L. Rice find that online forms of political participation–like friending or following candidates and groups as well as blogging or tweeting about politics–draw in a broader swathe of young adults than might ordinarily participate. Political scientists have traditionally determined that participatory patterns among the general public hold less sway in shaping civic activity among college students. This book, however, recognizes that young adults’ political participation requires looking at their online activities and the ways in which these help mobilize young adults to participate via other forms. Moffett and Rice discover that engaging in one online participatory form usually begets other forms of civic activity, either online or offline.

Web 2.0 and the Political Mobilization of College Students investigates how college students’ online activities, when politically oriented, can affect their political participatory patterns offline. Kenneth W. Moffett and Laurie L. Rice find that online forms of political participation–like friending or following candidates and groups as well as blogging or tweeting about politics–draw in a broader swathe of young adults than might ordinarily participate. Political scientists have traditionally determined that participatory patterns among the general public hold less sway in shaping civic activity among college students. This book, however, recognizes that young adults’ political participation requires looking at their online activities and the ways in which these help mobilize young adults to participate via other forms. Moffett and Rice discover that engaging in one online participatory form usually begets other forms of civic activity, either online or offline. Over the last 20 years, political campaigns and the media that cover them have been fundamentally altered by a mix of technology and money. This timely work surveys the legal, financial, and technological changes that have swept through the political process, putting those changes in context to help readers appreciate how they affect what the public learns, and doesn’t learn, about the candidates and lawmakers at the local, state, and federal levels. The encyclopedia offers a critical examination of a broad range of topics organized in a narrative, A-to-Z format. Written by journalists and political experts, the two volumes cover the major issues, organizations, and trends affecting both politics and the coverage of political campaigns. Some 200 entries treat everything from news organizations, think tanks, and significant individuals to questions concerning money, advertising, and campaign tactics. Objective, unbiased, and comprehensive, the encyclopedia is an unequaled resource for anyone seeking to understand American political journalism and news coverage in the 21st century

Over the last 20 years, political campaigns and the media that cover them have been fundamentally altered by a mix of technology and money. This timely work surveys the legal, financial, and technological changes that have swept through the political process, putting those changes in context to help readers appreciate how they affect what the public learns, and doesn’t learn, about the candidates and lawmakers at the local, state, and federal levels. The encyclopedia offers a critical examination of a broad range of topics organized in a narrative, A-to-Z format. Written by journalists and political experts, the two volumes cover the major issues, organizations, and trends affecting both politics and the coverage of political campaigns. Some 200 entries treat everything from news organizations, think tanks, and significant individuals to questions concerning money, advertising, and campaign tactics. Objective, unbiased, and comprehensive, the encyclopedia is an unequaled resource for anyone seeking to understand American political journalism and news coverage in the 21st century